Top 3 mistakes VCs make with QSBS

Qualified small business stock (QSBS) offers significant tax benefits, yet many venture capitalists (VCs) inadvertently take actions that can eliminate this advantage. Often, these mistakes are discovered too late, resulting in unexpected tax liabilities.

This blog aims to help emerging fund lawyers avoid the top three mistakes that can disqualify investments from QSBS status.

For a clear explanation of what qualified small business stock is, why it matters, and why it’s sometimes overlooked, check out the blog here.

The $75 million gross assets test and holding period flexibility

To qualify for QSBS, original issued shares must be acquired directly from a qualified small business taxed as a C-corporation. As of July 4, 2025, under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), the gross assets threshold has been raised to $75 million, expanding eligibility for larger startups. Additionally, the holding period requirements have been made more flexible:

- 3 years: 50% capital gains exclusion

- 4 years: 75% capital gains exclusion

- 5+ years: 100% capital gains exclusion (unchanged)

“Aggregate gross assets” refers to the amount of cash and the aggregate adjusted tax basis of property held by the company. This number is calculated by accountants and most often found on the company’s balance sheets.

Prior to July 4, 2025, most startups began to lose their QSBS status after two or three equity rounds, around Series B or Series C, as the total cash invested plus the value of a company’s gross assets often exceeded the $50 million threshold “immediately after” such investment. With the new threshold of $75 million, more startups may maintain QSBS eligibility through additional rounds of funding.

QSBS representation: Key insights from Aumni data

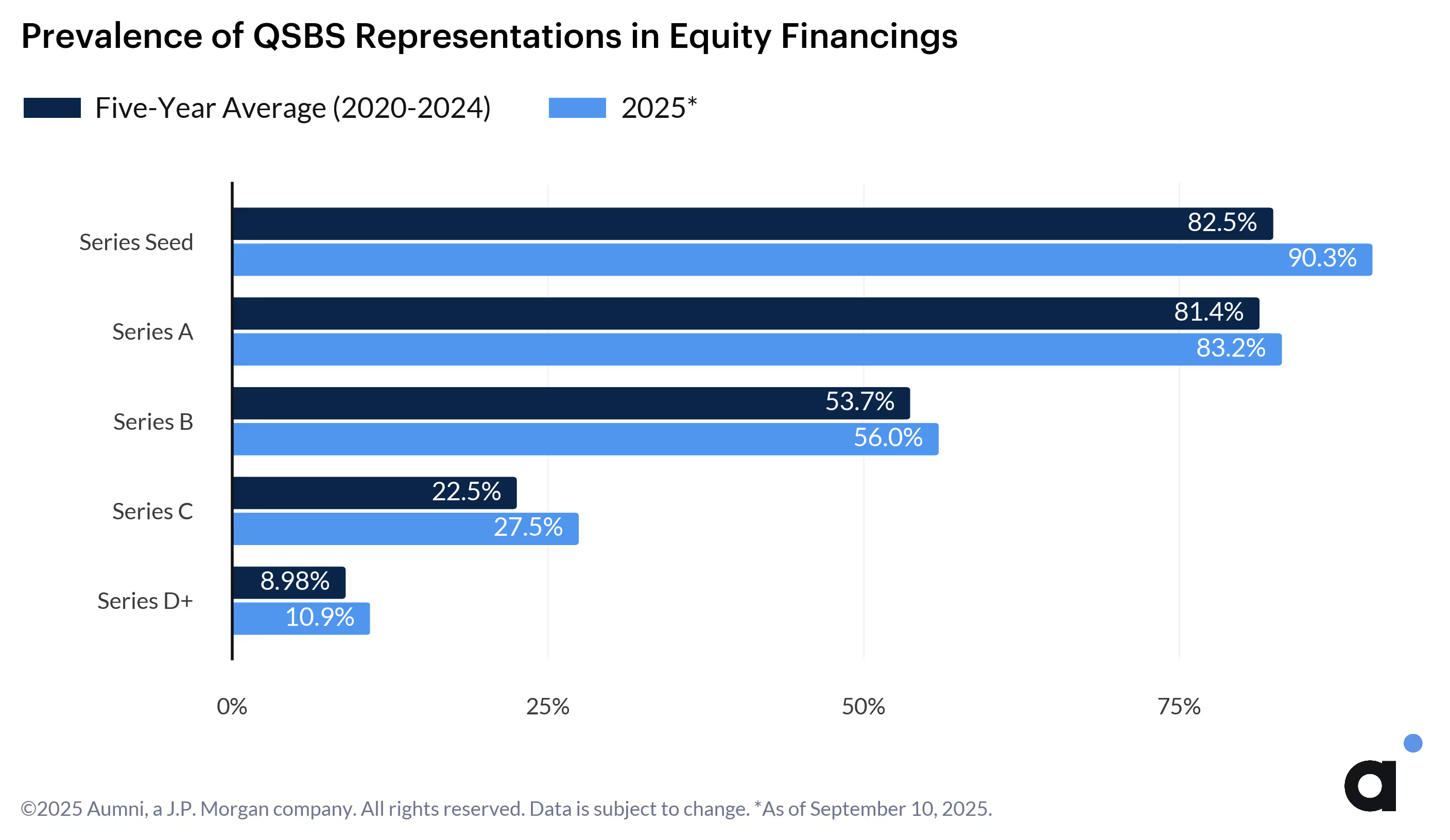

With the updated eligibility requirements in mind, it’s also important to understand how frequently QSBS representations appear in venture capital transactions. Aumni's VC data analytics platform, which has analyzed over 600,000 venture capital financing transactions, provides valuable insights into QSBS-related practices. Here’s what the data reveals about the prevalence of QSBS representations in 2025:

- QSBS representations prevalence is trending above the five-year average across all stages.

- Over 80% of Seed and Series A financings have QSBS representations.

- Less than 30% of late-stage financings have QSBS representations.

While QSBS representations are common in early-stage financings, some later-stage companies can still qualify for QSBS if they meet the requirements. This trend highlights a common misconception: QSBS eligibility is not determined by financing stage, but by whether the company continues to meet the statutory requirements. By understanding these requirements, fund managers and legal teams can maximize the benefits of QSBS for as long as their portfolio companies remain eligible.

Now, let’s explore the most common mistakes VCs make with QSBS—and how to avoid them.

Common QSBS mistakes and how to avoid them

Mistake #1: Tracking the wrong numbers

Valuation is irrelevant for QSBS purposes, the critical factor is the $75 million gross assets test. For instance, if a fund invests $5 million into a Series A round with a company valued over $100 million (pre-money) and $72 million of gross assets, the investment may not qualify as QSBS. However, with strategic adjustments and guidance from a tax speciality, it could pass the test.

Additionally, the treatment of SAFEs (Simple Agreements for Future Equity) can impact QSBS qualification. Whether a SAFE is considered equity or a prepaid forward contract can affect the outcome. Post-money SAFEs have equity-like features, but tax experts advise caution, as the IRS may treat SAFEs differently. Consulting with tax advisers is recommended to navigate this complex area.

Mistake #2: Poor record-keeping

Accurate record-keeping is essential. Aumni has found 30% of closing document sets have serious errors or are missing critical pages. Detailed balance sheets and equity documents are vital to support QSBS claims.

Incorporating standard QSBS language in deal documents can be beneficial. Common clauses include QSBS Rep & Warranty, QSBS Covenant, and Certification and 1-Page Checklist. Reporting requirements for QSBS benefits do not require special filing. Taxpayers must repost the sale of QSBS on Schedule D and Form 8949, with the IRS having three years to request additional documentation.

Mistake #3: Assuming QSBS applies

QSBS is a complex statute with potential pitfalls, including company redemptions, secondary transactions, investing more than 10% of a company’s assets, or investing in a portfolio company that isn’t engaged in an “active trade or business.”

Under section 1202, companies must meet active business requirements, which mandate that at least 80% of its assets be actively used in a qualified trade or business. Certain types of businesses do not meet this criterion, including:

- Trades of businesses involving the performance of services in fields such as health, law, engineering, architecture, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset is the reputation or skill of one or more employees.

- Banking, insurance, financing, leasing, investing, or similar business.

- Farming businesses, including the business of raising or harvesting trees.

- Businesses involved in the production or extraction of products for which a deduction is allowable under section 613 or section 613A (e.g., oil or gas properties subject to depletion).

- Businesses operating hotels, motels, restaurants, or similar establishments.

Qualified small business stock can be a powerful tax savings tool, but it requires careful planning and adherence to guidelines. It’s important to note that certain industries, such as FinTech, InsurTech, and insurance-related businesses, may have unique considerations under the QSBS statute. Gaining insights from IRS guidance can be beneficial for companies with hybrid business models that may touch on non-qualifying trades or businesses. Consulting with legal and tax advisers is essential to navigate the complexities of QSBS.

©2025 JPMorgan Chase & Co. All rights reserved. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. Member FDIC.

This material is not the product of J.P. Morgan’s Research Department. It is not a research report and is not intended as such. This material is provided for informational purposes only and is subject to change without notice. It is not intended as research, a recommendation, advice, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any financial product or service, or to be used in any way for evaluating the merits of participating in any transaction. Please consult your own advisors regarding legal, tax, accounting or any other aspects including suitability implications, for your particular circumstances or transactions. J.P. Morgan and its third-party suppliers disclaim any responsibility or liability whatsoever for the quality, fitness for a particular purpose, non-infringement, accuracy, currency or completeness of the information herein, and for any reliance on, or use of this material in any way. Any information or analysis in this material purporting to convey, summarize, or otherwise rely on data may be based on a sample or normalized set thereof. This material is provided on a confidential basis and may not be reproduced, redistributed or transmitted, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of J.P. Morgan. Any unauthorized use is strictly prohibited. Any product names, company names and logos mentioned or included herein are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

Aumni, Inc. (“Aumni”) is a wholly-owned subsidiary of JPMorgan Chase & Co. Access to the Aumni platform is subject to execution of an applicable platform agreement and order form and access will be granted by J.P. Morgan in its sole discretion. J.P. Morgan is the global brand name for JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its subsidiaries and affiliates worldwide. Aumni does not provide any accounting, regulatory, tax, insurance, investment, or legal advice. The recipient of any information provided by Aumni must make an independent assessment of any legal, credit, tax, insurance, regulatory and accounting issues with its own professional advisors in the context of its particular circumstances. Aumni is neither a broker-dealer nor a member of any exchanges or self-regulatory organizations.

383 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10017

.avif)